acespicoli

Well-known member

Had this long as signature everyone had to read past every time I posted,

This is better right a landing pad to find all the content in one place ?

Well my threads have become a little disorganized since I first got here

General off topic chat its all welcome here and here, well .... you know

So here is the TOC table of contents some of my stuff and some threads found of interest

Strain Selection

Grow Info Soil, Soiless, Watering

Lights

Medical

en.seedfinder.eu

en.seedfinder.eu

Recommended reading to @VerdantGreen for this list

to @VerdantGreen for this list

Fertilizers

phosphorus and potassium elements as follows:

So, for example, an 18−51−20 fertilizer contains by weight

Breeder Topics

Herbarium

What is a herbarium? A herbarium (Latin: hortus siccus) is a collection of plant samples preserved for long-term study, usually in the form of dried and pressed plants mounted on paper. The dried and mounted plant samples are generally referred to as herbarium specimens.

Resources

Tek

thought that was a booger but its snot

Hydro

Books

Tutorials

Biographys:

Photography

DIY huge index of ic diy Hits !

Im gonna clean this up one day... but how about that new sig ?

>Best>>>ibes

This is better right a landing pad to find all the content in one place ?

Well my threads have become a little disorganized since I first got here

General off topic chat its all welcome here and here, well .... you know

So here is the TOC table of contents some of my stuff and some threads found of interest

Strain Selection

- Seedbank Historical Data

- Genetics - Phyto Keys - Landrace- Phenotype - Chemotype - Yields - Terpenes - Viral

- Botany - Cannabaceae. Marijuana (Cannabis sativa). Herbarium Samples

- Collect - Sequencing <$300USD ea

Grow Info Soil, Soiless, Watering

- wiki soil-related_articles

- Why not just use field soil ?

- Prototype to AceS OPM's

- Media Physical Properties and Root Function

- Characteristics of Cannabis Roots

- AceS Organic Potting Mix's - PRE MIX AND CONTINOUS FEED - latest pests #207

- https://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/sa-7.pdf FPE fermented plant extract

- five-stage fermented colloidal molasses nutrient based organic hydroponics

- N, P, and K flowering stage of soilless cannabis production using RSM

- NPK Summary

- S.I.P Sub Irrigated Planter -

- Pests

- Fungus Gnats (Peat Based Mix ...you wanna read this)

- auto-water

Lights

Medical

Medical Marijuana Strains :: Pain (Medical Strain List)

Pain (Medical Strain List) Here the SeedFinder gathers and shares information on individual medical cannabis varieties.

- Preferred Medical Strain List Top 3 lack adverse effects

- Medical strain search help

https://cannabis-med.org/

https://cannabis-med.org/

Recommended reading

to @VerdantGreen for this list

to @VerdantGreen for this list- Principles of Plant Genetics and Breeding, 2nd Edition George Acquaah ISBN: 978-0-470-66475-9

- Principles of Plant Breeding 2nd Edition by Robert W. Allard ISBN: 978-0-471-02309-8

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vascular_tissue

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Membrane_transport

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agricultural_hydrology

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_balance#

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phloem#Function

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xylem#

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soil-plant-atmosphere_continuum

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vascular_bundle

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Molecular_diffusion

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photosynthesis

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chloroplast

Fertilizers

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plant_nutrition

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Labeling_of_fertilizer

- Converting nutrient analysis to composition

phosphorus and potassium elements as follows:

- P2O5 consists of 56.4% elemental oxygen and 43.6% elemental phosphorus by weight. Therefore, the elemental phosphorus percentage of a fertilizer is 0.436 times its P value.

- K2O consists of 17% oxygen and 83% elemental potassium by weight. Therefore, the elemental potassium percentage is 0.83 times the K value.

So, for example, an 18−51−20 fertilizer contains by weight

- 18% elemental nitrogen,

- 0.436 × 51 = 22% elemental phosphorus, and

- 0.83 × 20 = 17% elemental potassium.

Breeder Topics

- Different cannabis breeder references

- Back Cross and Inbreeding Depression

- Cannabis breeding ideologies

- DJ Short Book Cultivating Exceptional Cannabis

- DJ Short Article-General Irregularities-Anomalies Relating to Transgressive Segregation

- Mold Resistance

- haystack

- vintage pics II

Herbarium

What is a herbarium? A herbarium (Latin: hortus siccus) is a collection of plant samples preserved for long-term study, usually in the form of dried and pressed plants mounted on paper. The dried and mounted plant samples are generally referred to as herbarium specimens.

Resources

- Map of Asia

- Weather and Climate

- Time and Date

- Biology libre texts

- Gene sequences of THC/CBD etc

- 310 alleles, frequency 0.26 to 0.85 (average: 0.56)

Tek

thought that was a booger but its snot

- Legends

- Lambs Bread,

- Swazi Rooi (Red Beard)

- Oaxaca

- Train -

- himalayan rabbit recipe

- Dog Bud -

- Original Gangster -

- ECSD

- Haze

- PBub

- Domina

- G13

- P91

Hydro

- Bato

- Hydro Showdown

- Increased Cannabinoid Yields & Advanced Grow Teks

- rdwc-grow-along

- snypes-guide-to-rdwc

- root volume

- rdwc

Books

Tutorials

Biographys:

- atao

- BushyOldGrower

- ndn

- Sam

- bodhi

- coco

- nspecta

- good ole dog

- jahgreenlabel

- DJ short

- BubbleMan

- crazy-compose

Photography

DIY huge index of ic diy Hits !

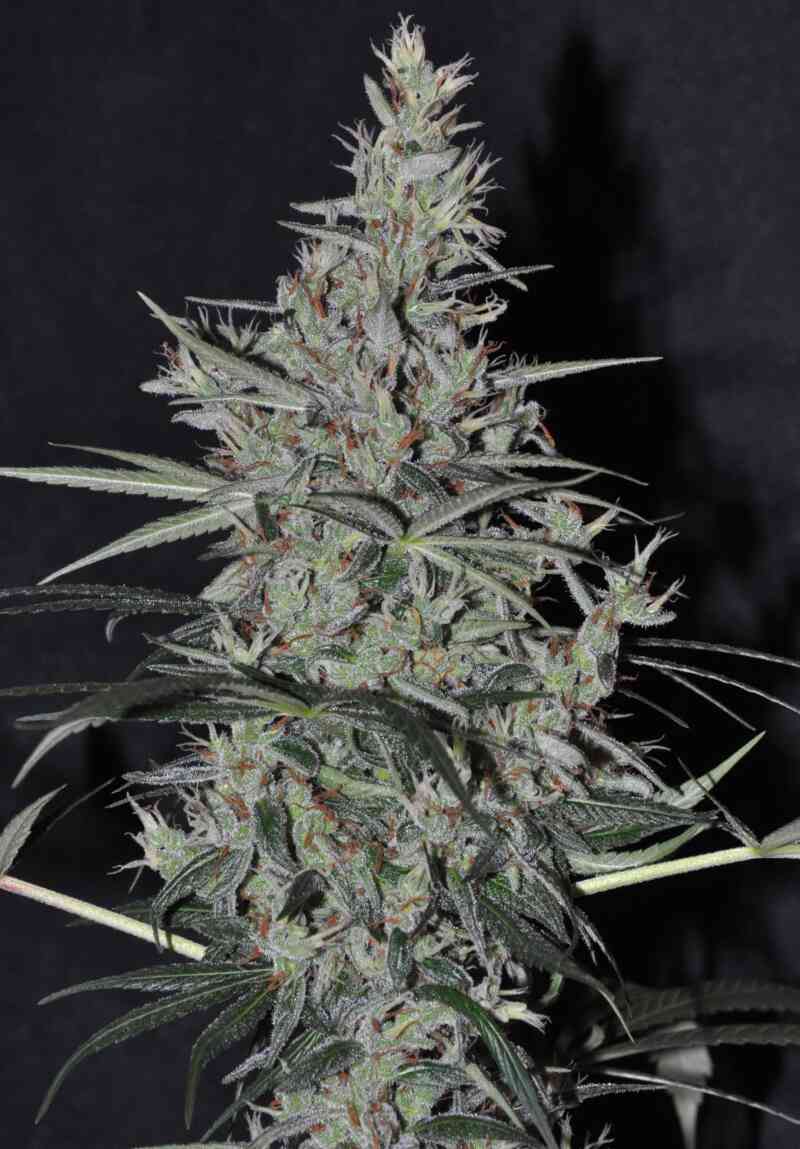

Im gonna clean this up one day... but how about that new sig ?

>Best>>>ibes

Last edited: